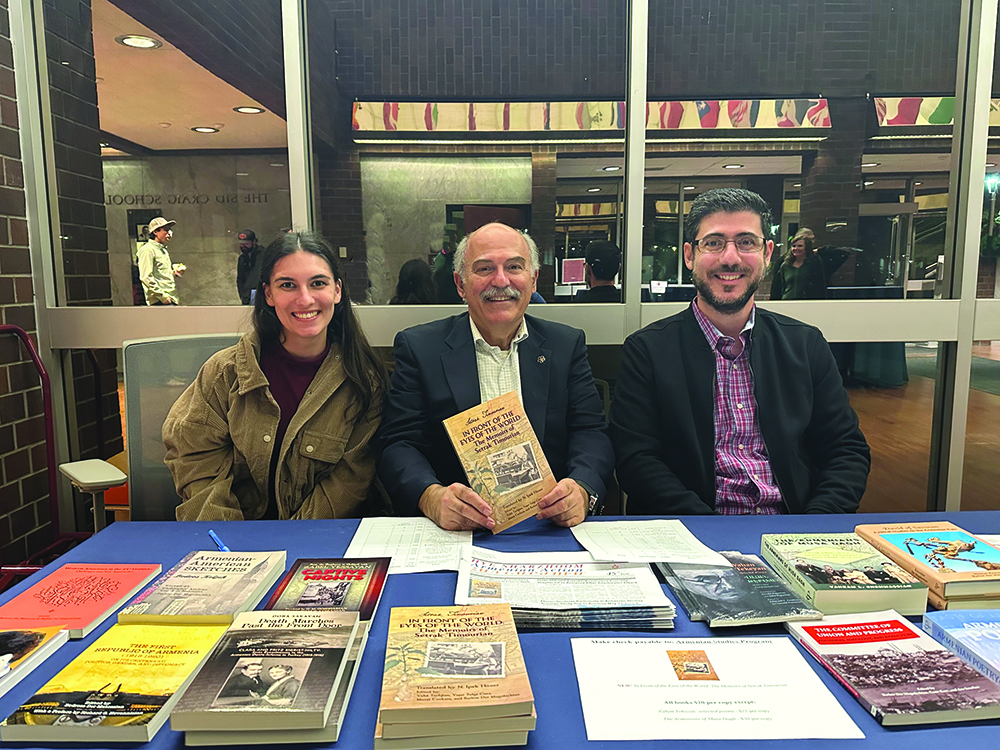

Photo: Natalie Agazarian

Careen Derkalousdian

Staff Writer

“Manuscripts are the living works of the Armenian people,” said Prof. Barlow Der Mugrdechian.

On Thursday, November 9, 2023, Prof. Der Mugrdechian, Berberian Coordinator of the Armenian Studies Program at Fresno State, gave a presentation on “Armenian Manuscript Painting: The Early Tradition.” Prof. Der Mugrdechian has taught courses in Armenian art and architecture at Fresno State for more than thirty-eight years. He is a former President of the Society for Armenian Studies and the General Editor of the Armenian Series at Fresno State. His presentation was part of the The Grace and Paul Shahinian Armenian Christian Art Series, sponsored by Mr. Dean Shahinian.

Prof. Der Mugrdechian began his lecture by discussing the creation of the Armenian alphabet in 406 A.D. by St. Mesrop Mashtots. He noted that one of the reasons for the creation of the alphabet was to promote and instill Christianity within the Armenian people. The majority of Armenian illustrated manuscripts are Gospels, with text from the books of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. These Gospel manuscripts are often called “illuminated,” a term which symbolizes how Jesus Christ brought light into the world; in the same way, the painting or illumination of manuscripts brings the light of Christianity to the Armenian people.

It is estimated that there are more than 30,000 Armenian manuscripts in existence today, of which over 10,000 are illustrated. The largest collection of Armenian manuscripts in the world is held in the Mesrop Mashtots Matenadaran in Yerevan, Armenia, where over 12,000 manuscripts are held in vaults under specific temperature and humidity conditions. The “Mayr Tsutsak” [Mother Catalog] on the Matenadaran website provides detailed information on many of the manuscripts held in the Library. The second largest Armenian manuscript collection is located at the St. James Armenian Monastery in Jerusalem, where over 4,000 manuscripts are held. Other notable manuscript collections are located in Venice, Italy; Vienna, Austria; and the Armenian Catholicossate of Cilicia in Antelias, Lebanon.

Prof. Der Mugrdechian highlighted the unique structure and order of Armenian manuscripts, beginning with the Eusebian Letter and Canon Tables and concluding with the colophon, or memorial note. The Eusebian Letter is essentially an explanation of how to use the following canon tables, which are an index that helps one find similar passages in the Gospels. Following the canon table are a series of Narrative Miniatures that depict significant events from the Bible. These are followed by images from the Life of Christ Cycle, the Portraits of the Evangelists, and the Gospel text itself. A memorial note by the manuscript’s scribe called the Colophon signifies the end of the manuscript.

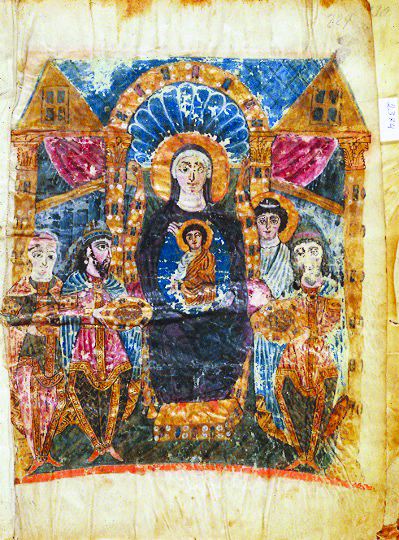

Prof. Der Mugrdechian spoke about three early Armenian manuscripts that each follow this unique structure: the Etchmiadzin Gospel, the Queen Mlke Gospel, and the Translator’s Gospels. The Etchmiadzin Gospel, dating back to 989 A.D., was executed at the monastery of Noravank in the Siunik province. Its ivory binding depicts a central motif of Mother Mary holding the infant Jesus, with events from Mary’s life surrounding the central image. Prof. Der Mugrdechian noted the classicizing style of the manuscript, a style that was dependent on models of Byzantine manuscripts. Upon examination of the Eusebian Letter of the Etchmiadzin Gospel, one can see that Armenian manuscripts utilize vibrant colors. The text of the Eusebian Letter is framed by an arch adorned with pomegranate trees and birds, representing eternal life and virtues, respectively. An interesting aspect of this manuscript is that it contains a painting depicting the sacrifice of Abraham and Isaac from the Old Testament, where God rescued Abraham’s son and the Covenant between God and Man was established. This artistic choice parallels God sacrificing his own son, Jesus Christ, in the New Testament.

The late Sirarpie Der Nersessian, a pioneer Armenian art historian at Wellesley College and Dumbarton Oaks, upon further examining the Etchmiadzin Gospels, demonstrated that the “Final Four” of the paintings from manuscript actually date back to the late 6th century, much earlier than the manuscript’s original date of creation, and prior to the Arab advance into Armenia.

Prof. Der Mugrdechian also discussed the Queen Mlke Gospel, a prized possession of King Gagik Artsruni’s wife, Mlke, who ruled in the 10th century. This manuscript is older than the Etchmiadzin Gospel and dates back to the mid 9th century. It also utilizes the classicizing style of the Byzantines and contains only one surviving painting, depicting the Ascension of Christ. It is elegantly illuminated and its Eusebian Letter and canon table are lavishly decorated with birds, plants, and Nilotic scenes.

In contrast with the classicizing Etchmiadzin and Queen Mlke manuscripts, the 10th c. Translator’s Gospel, housed in the Walters Gallery in Baltimore, Maryland, represents a different style, referred to as monastic or provincial, terms that highlight its simplistic look. This style of manuscript painting is the oldest Armenian native style and is unaffected by Byzantine or Syriac techniques. Sarkis the Priest, the scribe of the Translator’s Gospel, uses simpler paint strokes than that of his predecessors.

Prof. Der Mugrdechian concluded his presentation by noting the significance of these early manuscript traditions. Not only do they reflect the diversity in Armenian art, but they set the foundation for the later 11th century Armenian miniature painting, a productive period for the creation of illuminated manuscripts.

Hye Sharzhoom Armenian Action

Hye Sharzhoom Armenian Action