Dr. Jonathan Conlin

Special to Hye Sharzhoom

Author of the definitive biography of Mr Five Per Cent, Dr. Jonathan Conlin reflects on a fabled meeting between the oil magnate and philanthropist Calouste Gulbenkian and William Saroyan.

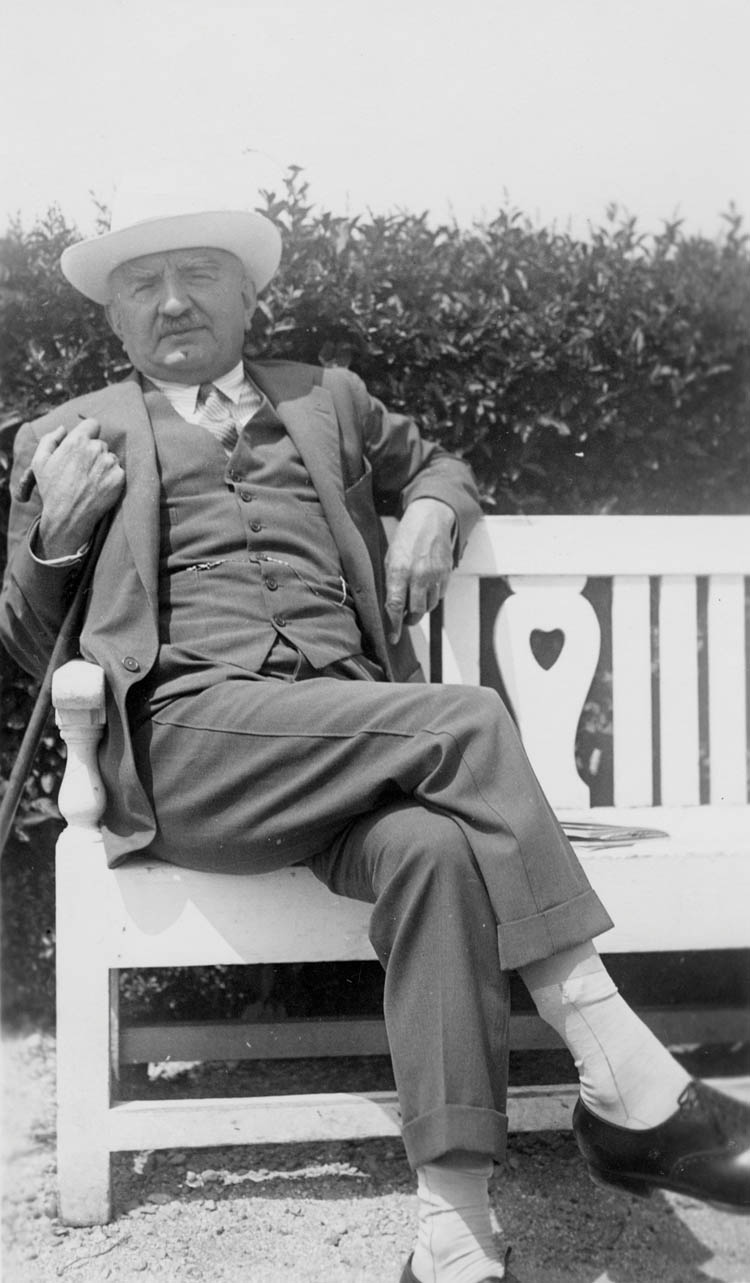

Les Enclos, c. 1949.

I should begin with a confession: I did not read Saroyan’s accounts of meeting Gulbenkian until April 2019, several months after my biography was published. This was not the result of ignorance. At several points during my five years of research into the Armenian maecenas-superman several people had referred me to that late collection of autobiographical essays: Letters from 74 rue Taitbout or Don’t Go But If You Must Say Hello to Everybody (1968). In an essay in that volume entitled simply ‘Calouste Gulbenkian’ Saroyan describes getting to know the reclusive fellow Armenian during a stay in Lisbon in 1949. The essay refers in passing to an earlier novella, “The Assyrian,” published in a 1950 collection of the same name, in which a thinly-disguised Gulbenkian also makes an appearance, albeit as an Arab/Assyrian named “Curti Urumiya.” I read them belatedly and somewhat shamefully, during a visit to Fresno State’s Armenian Studies Program.

The idea of Saroyan and Gulbenkian meeting in 1949 seemed unlikely. Saroyan certainly did pass through Lisbon in May 1949, a pivotal point in his personal life and career. As Harry Keyishian has observed, around this time Saroyan’s writing “took on a darker hue…he faced up to the unhappy human facts of failure, betrayal, and irretrievable loss.” Lisbon and the neighbouring resort of Estoril provided a fitting setting for troubled reflection. Their reputation as glamourous bolt-holes for refugees, spies and exiles had been burnished to a shine by the Second World War, when Lisbon became popularly known as “Casablanca II.” The ideal place for an Armenian-American bird to perch, therefore, hovering and havering between the New World and the Old, past and future. Gulbenkian, the fabulously-wealthy Armenian recluse ensconced at the opulent Hotel Aviz offered the ideal father confessor. And Saroyan had much to confess: his marriage to Carol Marcus had broken down, and he was facing the prospect of separation from his two beloved children.

Did Saroyan check into the Aviz? Was he introduced to Gulbenkian by the hotel manager? Did the pair establish what Saroyan calls “a personal connection” over successive lunches and dinners in the hotel’s restaurant, between long stints at the roulette tables of Estoril? The short answer is “almost certainly not.” Gulbenkian had been resident at the Aviz since 1942. By 1949 his love of privacy would have been well-known to the hotel’s staff, who were well paid to keep strangers away. Should they ever fail in their duties, the feared political police were on hand, equally incentivized to protect “Mr Five Per Cent” from unwanted attention. The Aviz was a fortress. The stories’ contention that an Armenian visitor would be brought to Gulbenkian’s attention, simply by dint of being Armenian, is implausible. If the many self-described “cousins” besieging Gulbenkian in these years did not breach the cordon, it is unlikely Saroyan did.

Nor would Saroyan’s literary reputation have served as laisser-passer. Gulbenkian was uninterested in literature. Though he was corresponding with the renowned French poet Alexis Leger (known by his nom de plume Saint-Jean Perse), Gulbenkian had got to know Leger back in the 1930s, in the latter’s capacity as a senior diplomat at the French Foreign Ministry. As their correspondence (since published) demonstrates, Leger was careful not to bore Gulbenkian by referring to his literary activities. The ‘Gulbenkian’ of the two pieces displays several traits which we know Gulbenkian did not have: Gulbenkian did not hail from Bitlis, did not speak Arabic. Decades of stern letters to his son Nubar betray a deep-seated hatred of gambling. The idea of Gulbenkian offering to help Saroyan out with any gambling debts is fantastical.

Even the language Saroyan uses in describing his purported relationship with Gulbenkian (“a personal connection”) smacks of a hail-fellow-well-met approach to interpersonal relations profoundly alien to Gulbenkian’s manner. This was not a man to be taken by storm. As Sir Kenneth Clark observed in his own memoirs, Gulbenkian was stiff, formal, wont to speak “as one potentate to another.” Records for this period of Gulbenkian’s life are extensive, yet no correspondence from Saroyan survives in the Gulbenkian archives in Lisbon. All that I could find was a copy of a French translation of “The Assyrian” with the relevant passages highlighted in red pencil. Gulbenkian (or a member of his entourage) did read Saroyan’s account of this meeting in translation, therefore. But there is no evidence to suggest that the meeting actually happened.

That is very far from saying that these pieces are without interest. On the contrary, they reveal a lot about Saroyan’s Armenianness, as well as public perceptions of “Mr Five Per Cent” in Gulbenkian’s final years, when he became celebrated as the world’s richest man. Even if Saroyan’s version of checking in to the Aviz doesn’t check out, therefore, that does not lessen the importance of “The Assyrian” and “Calouste Gulbenkian.” What, then, can we learn about both men from Saroyan’s account of a meeting that never happened?

Gulbenkian’s fortune had been built by an eye for detail, profound suspicion of human motivations and relentless pursuit of profit. Challenging material for Saroyan. As Saroyan notes “I have always believed that money ought not to go to a few lucky people in the world as long as there is poverty of any kind among the majority of the people.” Gulbenkian would have snorted at that “lucky”; his fortune had been built on hard work. Saroyan’s ‘Gulbenkian’ takes a stoical view of his own fortune. When he raises the possibility that the Middle East will fall under the sway of the Communist bloc, leading to the confiscation of his famous share of Middle East oil production, ‘Gulbenkian’’s reaction is supine: “Oh no, if it happens, I shall not mind at all…I might find time to concern myself more with art.” Gulbenkian certainly did display a softer side in his final years in Lisbon, and was fond of describing himself as “a philosopher.” This side was only shown to a handful of intimates, however, and certainly did not extend to this degree of easy come-easy go.

‘Gulbenkian’ is thus a projection of Saroyan’s own persona. Saroyan takes comfort from the conceit that big business is built on “luck,” just another form of gambling. It serves to cut the richest man in the world down to size. So does the idea of Gulbenkian as fellow Armenian exile. “In a sense, we were both homeless, we had no geographical country of our own as we had once had and as we had ever since wanted to have, excepting the very small portion of what was once our country, which had become a part of Soviet Russia in 1921.” Whether Saroyan actually viewed the Republic of Armenia as the true home of Armenians is debatable: he often presents Armenia as a space Armenians carry with them, in diaspora.

Despite having ample means to assist the fledgling sovereign national home back in 1919, Gulbenkian had never shown much interest in a “geographical country of our own.” Like Saroyan, he found much of “patriotic” discourse of Dash-nak and Hnchak wearisome: it was best for Armenian refugees to make new lives for themselves abroad, rather than hanker for “return” to a “geographical country” of which few if any of them had personal experience. Saroyan is therefore closer to the mark when addresses “Gulbenkian” and himself as people who “simply did not belong to a geographical and political country that was our own. We lived and worked here and there, but it was known that you were Armenian and that I was Armenian, and at lunch we acknowledged to each other instantly that we were. We spoke our language, and enjoyed doing so.”

As Leger’s letters to the real Gulbenkian show, Saroyan was not the only author to appreciate the opportunity Gulbenkian afforded to project their own sense of exile and then wallow in it. Leger was living in exile in Washington, where he had served during the war as unofficial ambassador for a France of the mind, a France very different from the puppet state of Pétain’s Vichy. Living off his wits, Leger, like Saroyan, probably took comfort from the idea of having so much in common with a man of fabled wealth, a man who might become a patron. While Saroyan looked to Armenia as the lost home he and Gulbenkian held in common, for Leger it was Les Enclos, Gulbenkian’s private estate in Normandy – an estate which Leger wrote about extensively, yet never visited.

The bulk of Saroyan’s account, the tid-bits about “Gulbenkian’s” diet and relations with hotel staff, were already the stuff of public record, and hence do not reveal much. One has only to read Life magazine’s 1950 profile to find the same facts rehearsed, albeit in a less flattering manner. At the end of the day it was not Gulbenkian’s diet which fascinated Saroyan, but a certain idea of Gulbenkian. Gulbenkian as father-confessor and provider, who succeeded where Saroyan’s own father had failed, a glamourous Armenian with an international fame.

In the 1950s many Armenians looked at Gulbenkian and saw a “token Armenian”: someone who had repeatedly failed to follow the philanthropic and political script, not only in 1919, but in his roles as Ottoman Turkish diplomat (1909-1914), as president of the AGBU (1930-1932), and, finally, as founder of the great Gulbenkian foundation, which many Armenians felt ought to have done more for Armenia. But when Saroyan looked at Gulbenkian he saw something rather different. He saw himself, the true Armenian.

Jonathan Conlin teaches history at the University of Southampton, UK. His biography of Gulbenkian, entitled Mr Five Per Cent: the Many Lives of Calouste Gulbenkian, World’s Richest Man was published in English by Profile Books in January 2019. A Portuguese edition has also been published, and further editions in Turkish (Can Yayinlari) and Russian and Eastern Armenian (Edit Print) are in preparation. He can be reached at j.conlin@soton.ac.uk

Hye Sharzhoom Armenian Action

Hye Sharzhoom Armenian Action