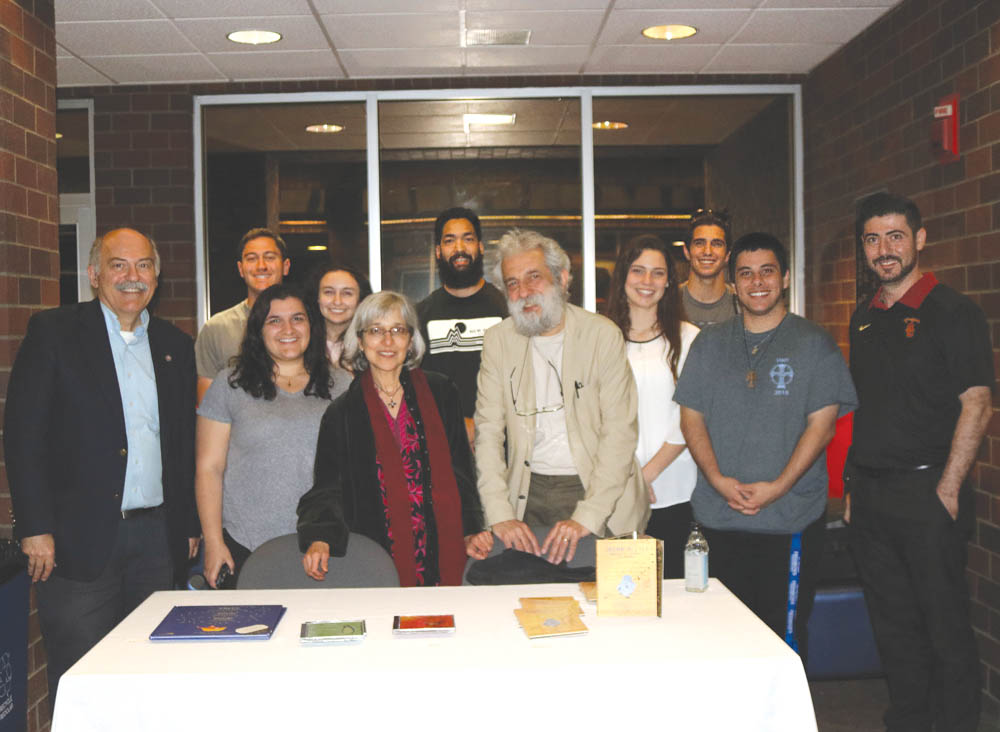

Photo: Andrew Hagopian

David Safrazian

Staff Writer

“Each time we sing a song, though it has been sung before, it is new,” said Aram Kerovpyan. Armenian church music was nearly completely torn away from its homeland since the Armenian Genocide in 1915.

Musicologists Aram and Virginia Kerovpyan visited Fresno State on Wednesday, May 1, to present a new film, Singing in Exile, a prize-winning documentary by Nathalie Rossetti & Turi Finocchiaro.

The film follows the journey of Aram and Virginia Kerovpyan through historic Armenia, where the culture of Armenian liturgical songs was born. Accompanying them on this journey were Jarosław Fred and actors from Theatre Zar in Wrocław, who were researching a new play on the Armenian Genocide.

“Singing in Exile” presents the fragile transmission of an ancient, critically endangered singing tradition. The actors learned about the presence of the rich Armenian culture where singing and church hymns were a major part of the culture.

Armenians still exist today due to the survival of the Armenian Church, which allows the hymns to be sung and sung again throughout the diaspora.

The Kerovpyans visited historic Armenia and discovered many ruined churches that were destroyed in the Genocide, and they discussed the survival of the Armenians. “How can you assimilate to something that’s not your culture?”, Aram said. “Falsify your identity.” Armenians are always true to their ethnic roots. “If you go to Armenia today, you will hear ghosts singing,” said Kerovpyan in the film. The sounds of music create stories and memories that are able to connect the past to the present.

The story of slain journalist Hrant Dink was woven into the story as the Kerovpyan’s traveled to Istanbul, where they engaged in discussions about identity and the Genocide. “Everything I couldn’t experience in my youth I can experience now when I return to Turkey.” Kerovpyan spent many years in Istanbul.

“Traditional Armenian church singing is threatened because it was torn away from its land. It was forced to live on different lands, in lands of adoption,” said Kerovpyan.

Near the end of the film, Theatre Zar performs elements from their play among the ruins of an Armenian church.

Aram Kerovpyan said that he plans to make a project dedicated to the Armenian Genocide. As Aram and Virginia were traveling to different villages, they would talk to the locals to get their perspectives on the Genocide. Though Armenians have lost their homeland and church traditions, this film shows that there is hope that these traditions can be taught to the new generations.

Virginia Pattie Kerovpyan was born in Washington, D.C. and moved to Paris in the 1970’s. She has performed and recorded with various early music ensembles, as well as contemporary music. Soloist of the Kotchnak and Akn ensembles, she has specialized in Armenian song since 1980.

Aram Kerovpyan was born in Istanbul, Turkey and learned to play the kanoun and studied the Near Eastern music system with Master musician Sadeddin Öktenay.

Moving to Paris, Kerovpyan joined the Kotchnak ensemble, performing Armenian folk and troubadour music and in 1985, established the Akn ensemble specializing in Armenian litur-gical chant. He holds a Ph.D. in musicology and publishes about modal theory and history of Armenian liturgical music.

Hye Sharzhoom Armenian Action

Hye Sharzhoom Armenian Action