Photo: ASP Archive

Carina Tokatian

Staff Writer

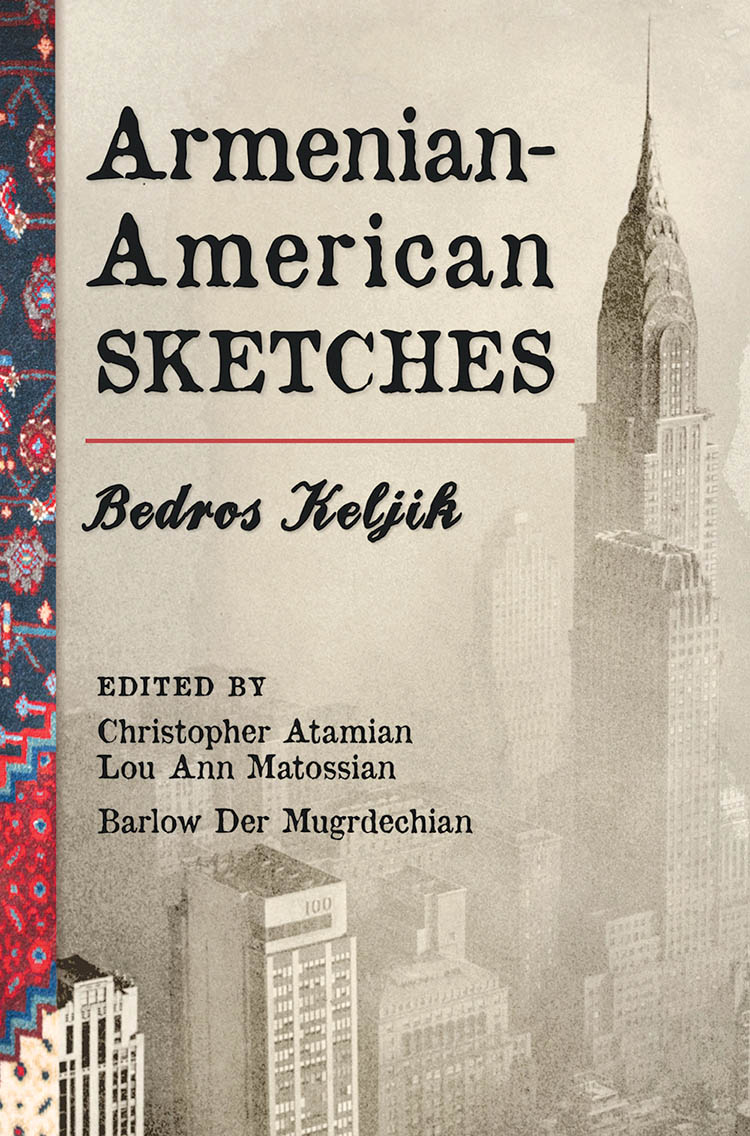

“Observe your surroundings before looking afar” was the sagacious advice that Armenian-American writer Bedros Keljik recalled his schoolteacher, Hovhanness Tlgadinsti, imparting to his students. In his Armenian-American Sketches (Amerigahay Badgerner), Keljik’s writing stands as a manifestation of this maxim; he invites his readers to enter the vivid culture surrounding his experiences as an Armenian-American.

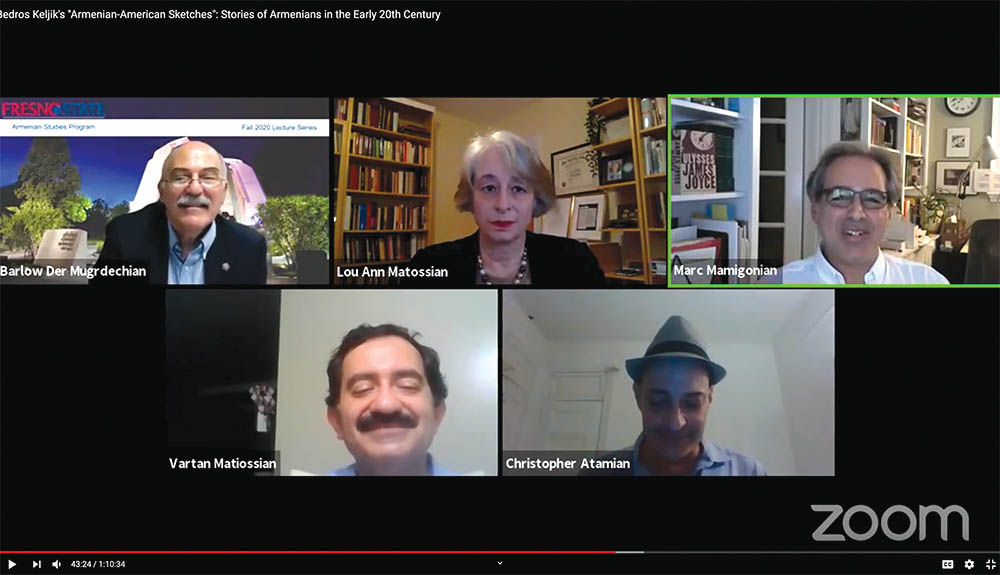

On Sunday, September 27 the Armenian Studies Program invited co-editors Christopher Atamian, Dr. Lou Ann Matossian, Prof. Barlow Der Mugrdechian, translator Vartan Matiossian, and moderator Marc Mamigonian to present Bedros Keljik’s book, Armenian-American Sketches, translated for the first time into English. Included in this volume are also Keljik’s biography prepared by his grandchildren, Mark and Thomas Keljik and Keljik’s translation of Roupen Zartarian’s “How Death Came to the Earth.”

The presentation, streamed on both YouTube and Zoom, was sponsored by the Armenian Studies Program and co-sponsored by the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research (NAASR), the Armenian Cultural Organization of Minnesota (ACOM), and the Society for Armenian Studies (SAS).

Armenian-American Sketches is the eighth volume in the Armenian Series of The Press at California State University, Fresno. Prof. Barlow Der Mugrdechian of the Armenian Studies Program is the editor of the Armenian Series.

Armenian-American Sketches is the eighth volume in the Armenian Series of The Press at California State University, Fresno. Prof. Barlow Der Mugrdechian of the Armenian Studies Program is the editor of the Armenian Series.

Matossian began the discussion with a biographical account of Keljik’s life. Bedros Arakel Keljik was born in the region of Kharpert, also known as Harput, in 1874. It was his school principal and teacher Hovhannes Tlgadinsti who paved the way for his future as a writer. When he was just sixteen years old, Keljik emigrated to the state of Massachusetts where he was a factory worker. He later moved to Boston where he began to take on a new role as a political activist for the Hnchakian Party.

In 1892 Keljik married Zabel Kertikian, and the two of them moved to Chicago, Illinois in 1896. It was here that Keljik began to emerge as an entrepreneur as he sold oriental rugs in a department store. Simultaneously, Keljik managed to graduate from the Kemp College of Law and campaign for the Democratic Party. In 1899 the Keljiks moved to St. Paul, Minnesota where he established his own oriental rug business. This business was eventually passed down through one of Keljik’s three offspring, Emerson Keljik, and is currently owned by the third generation of Keljiks.

“His own story was at least as colorful as any of his fictional characters,” stated Matossian. In addition to all the other colorful titles that Keljik had acquired, translator and writer were added to his list. Keljik was not the only one, however, who had a passion for writing. His brother, Krikor Keljik, and nephew, Vahan Totovents, shared in this passion. Keljik was also involved with an Armenian literary society during his time in Boston. It is through this group that he became acquainted with woman’s suffragist Alice Stone Blackwell. Ohannes Chatschumian, a good friend of Blackwell’s, was responsible for introducing her to this society, and the two of them began translating some Armenian poetry into English. Unfortunately, Chatschumian passed away without finishing the project, so Keljik took Chatschumian’s place and helped Blackwell with the translations. Matossian noted how the translation process usually entailed Keljik providing the literal translations and Blackwell refining those into idiomatic English.

Keljik and Blackwell’s timing was impeccable. Matossian ex-plained how amidst the Hamidian Massacres, “suddenly there was a need to introduce Americans at large to Armenian culture and literature in order to bring to their attention what was going on with Armenians in the Ottoman Empire at the time.” In addition to translations, Keljik contributed some of his own pieces to the stock of Armenian literature circulating in America. Matiossian remarked how Keljik relied on “a crisp and simple style of writing” to capture the Armenian-American’s experiences in the late 19th century through the early 20th century.

Marc Mamigonian equated Keljik’s style to that of Irish novelist James Joyce as both composed “a chapter on the moral history of their countries.” In contrast, Prof. Der Mugrdechian compared Keljik’s work to that of William Saroyan, mentioning how “they both bring to life characters long since gone.” On the other hand, Der Mugrdechian acknowledged that there are some clear differences between Saroyan and Keljik’s writing.

“Keljik portrays the often-difficult struggles and challenges that the early Armenian settlers went through,” Der Mugrdechian asserted. On a similar note, Mamigonian emphasized how “these are not romanticized portraits… many of the characters are cunning, maybe a little crooked. Some are honest and others are too naïve maybe for their own good.”

But where there may be flaws or struggles, there is also humor contained in Keljik’s works. For instance, Atamian explained how Keljik’s short stories are hilarious in that “there is every possible stereotype you want inside these pieces about Armenians, Jews, Irish people, drunkards, women, men, clergymen.” At the same time, there is also an element of nostalgia. For instance, Mamigonian observed how these stories published in the 1940s look back on the Genocide. “There is a definite sense of what has been lost not just by the genocide but leaving the homeland,” he reflected. The wealth of themes found in the margins of his stories, places Keljik’s writing under several genres. For example, Atamian noted how Keljik’s descriptions of places in Boston which no longer exist categorize Keljik’s texts as American history. And yet, as Atamian observed, these short stories can also be identified as Armenian history, ethnic history, and other categories.

The translation project would have not been possible if it were not for a series of coincidences. These coincidences began when Mark Keljik, Bedros’ grandson, visited the Library of Congress. He discovered his grandfather’s book when typing the family name into a card catalog. The family then hired Armenian translator and journalist Aris Sevag to translate seven of Keljik’s stories and Matossian also translated one story which all appeared in the Ararat Quarterly.

Coincidentally, Atamian who wrote for Ararat under Sevag’s leadership, was piqued in Keljik after coming across some of his translations. And by a third coincidence, Atamian happened to be having dinner with Matossian in a Georgian restaurant when he discovered Matossian’s knowledge of Keljik and interest in the project. Unfortunately, Sevag was unable to complete the translation process due to his untimely passing. However, Atamian and Matossian approached Der Mugrdechian three years ago, and the project sprouted from there.

Despite all the coincidences, Atamian commented how there also “has to be a consciousness amongst Armenians, first of all, that cultural work is work.” He explained how these sorts of projects are full-time jobs. Mamigonian highlighted the current “lack of institutionalization” and “dependence on individual initiatives solely.” Atamian also points to financial support and the critical mass to help support these projects. As Matiossian concluded, “why the book could have gone unnoticed to anyone living in Armenia unless he or she was a scholar is a testament to the fact that so many treasures are hidden behind the curtain of language. And it takes so little to open that curtain and uncover so many of those treasures.”

Armenian-American Sketches is available through:

NAASR bookstore-

https://naasr.org/products/armenian-american-sketches?_pos=1&_sid=c1952bab1&_ss=r

Abril bookstore-

http://www.abrilbooks.com/armenian-american-sketches.html

Hye Sharzhoom Armenian Action

Hye Sharzhoom Armenian Action