Photo: ASP Archive

Careen Derkalousdian

Staff Writer

“I argue that through a focus on the lived experience of children during genocide, we can build a comparative framework for the global study of indigenous genocide,” said Dr. Keith Watenpaugh. “I make this argument because during most genocides, there is a systematic and shared pattern of the treatment of children.”

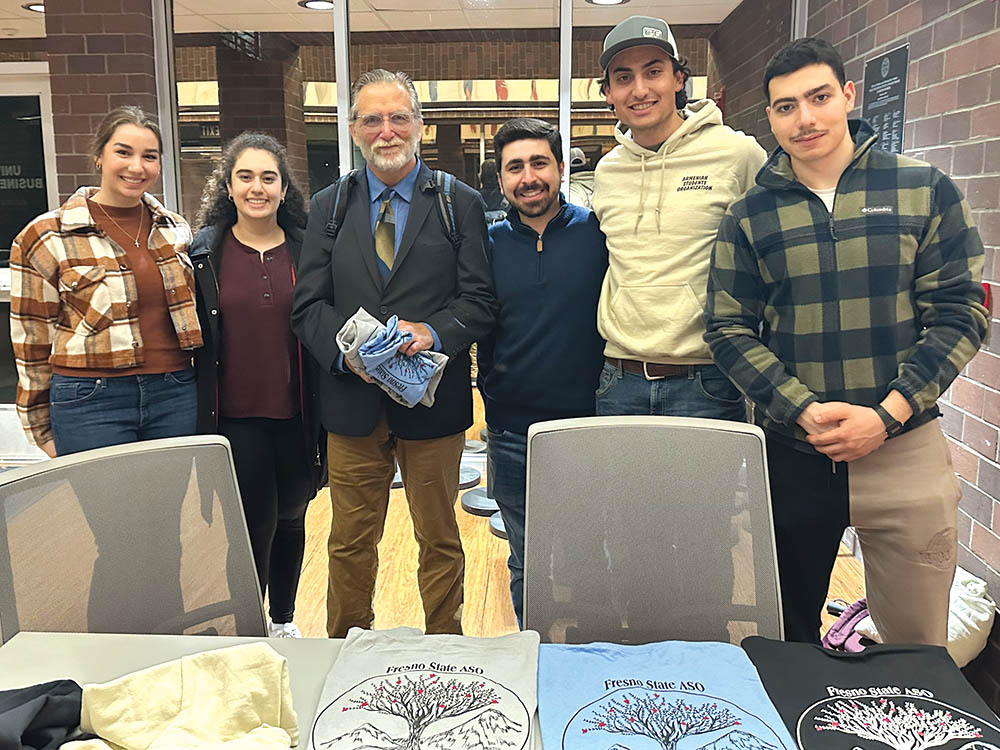

On Thursday, February 1, 2024, Dr. Keith Watenpaugh, Professor and Founding Director of Human Rights Studies at the University of California, Davis, discussed the parallels between the Armenian and Native American genocides. His talk, “Eradicating Culture, Erasing Lives: Children and the Armenian and Native American Genocides” focused on the erasure of childrens’ ethnic identity through state-governed boarding schools. The presentation, organized by the Armenian Studies Program, was held at the University Business Center and made possible through the Florence Elaine Hamparson Armenian Memorial Fund.

A year prior to the 100th commemoration of the Armenian Genocide, Dr. Watenpaugh received a phone call. On the line was Houri Boyajian, a friend of his mother-in-law, Sona Zeitlian, award-winning educator and author. Boyajian shared with Dr. Watenpaugh a thick manuscript – the memoir of her father Karnig Panian, an Armenian Genocide survivor. The manuscript details Panian’s survival of the Armenian Genocide and the subsequent attempt of Turkish officials to transform him and other orphaned children into Turks. In 2015, this memoir titled Յուշեր Մանկութեան եւ Որբութեան (Memories of Childhood and Orphanhood), was published as Goodbye Antoura, a book that is among Stanford University Press’ bestsellers. It is taught in high schools and read by Dr. Watenpaugh’s students in his comparative genocide course, the country’s largest of its kind.

Upon the order of Cemal Pasha, one of the main orchestrators of the Armenian Genocide, Panian and other children who were orphaned by the genocide were rounded up for “public health reasons” and taken to orphanages, where they were to be Turkified.

Dr. Watenpaugh discussed a passage from Goodbye Antoura in which Panian provides merely a glimpse of the inhumane treatment he and the other orphans suffered. Dr. Watenpaugh also noted the rigorous Muslim education, forced conversion, and brutal beatings that they had to endure. Simply whispering a prayer or speaking Armenian resulted in excruciating consequences.

Within his field of genocide studies, Dr. Watenpaugh explains that there has been a discussion, or argument, regarding indigenous genocide and whether or not it should be labeled as such. He argues that what happened to indigenous people in the United States should be considered genocide as it is comparable to what the Armenians faced in 1915.

“For me, these similarities were not coincidences,” said Dr. Watenpaugh. “They were a part of a process of genocide.”

Dr. Watenpaugh highlighted one of these similarities – that many Native American children were taken to schools resembling Panian’s. When comparing photos of Panian’s orphanage with photos from “Indian” boarding schools, he stressed that the images are very similar, with young children being shorn of their hair and dressed in uniforms. He also frequently saw photos of children lined up in front of brick buildings as an “ubiquitous image.”

Upon comparing these images, Dr. Watenpaugh sought to find a memoir similar to Panian’s written by a Native American author. With the help of his colleagues, he found the memoir Pipestone: My Life in an Indian Boarding School, written by Adam Fortunate Eagle, who was taken to the institution just 20 years after Panian was forced into Turkification. Fortunate Eagle’s experience parallels that of Panian. He recalls being told that his civilization was worthless. He was forced to dress in a certain way and was prevented from speaking the language of his people, the Chippewa.

Dr. Watenpaugh also described the Dawes Act of 1887, which sought to solve the “Indian Problem” by erasing the cultural and political identity of Native Americans. Those familiar with the field of Armenian Genocide studies can recognize that similar, dehumanizing verbiage was used by the Ottoman Turks to refer to the Armenians as a “problem” that needed to be eradicated.

Dr. Watenpaugh mentioned a quote by Richard Henry Pratt, who was an American military officer and founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in 1879. Pratt’s notorious quote reads: “Kill the Indian, Save the man.”

Dr. Watenpaugh emphasized that in saying this, Pratt was not referring to killing the man, but was instead talking about eradicating his culture. Dr. Watenpaugh highlighted this erasure of culture as a key similarity between Panian’s and Fortunate Eagle’s experiences and regarded this as a central policy of genocide, not a byproduct.

Dr. Watenpaugh concluded his talk by arguing for a necessary reconceptualization of the Armenian Genocide experience as one of indigenous genocide.

Dr. Watenpaugh believes that this reframing will represent solidarity with other indigenous peoples struggling against state-based denial and fighting for recognition.

Hye Sharzhoom Armenian Action

Hye Sharzhoom Armenian Action