Arshak Abelyan

Staff Writer

“The magician works his alchemy not upon stone and gold but upon something deeper in us, the uniquely human gift to perceive language,” stated Dr. James Russell, describing the poet Misak Medzarents.

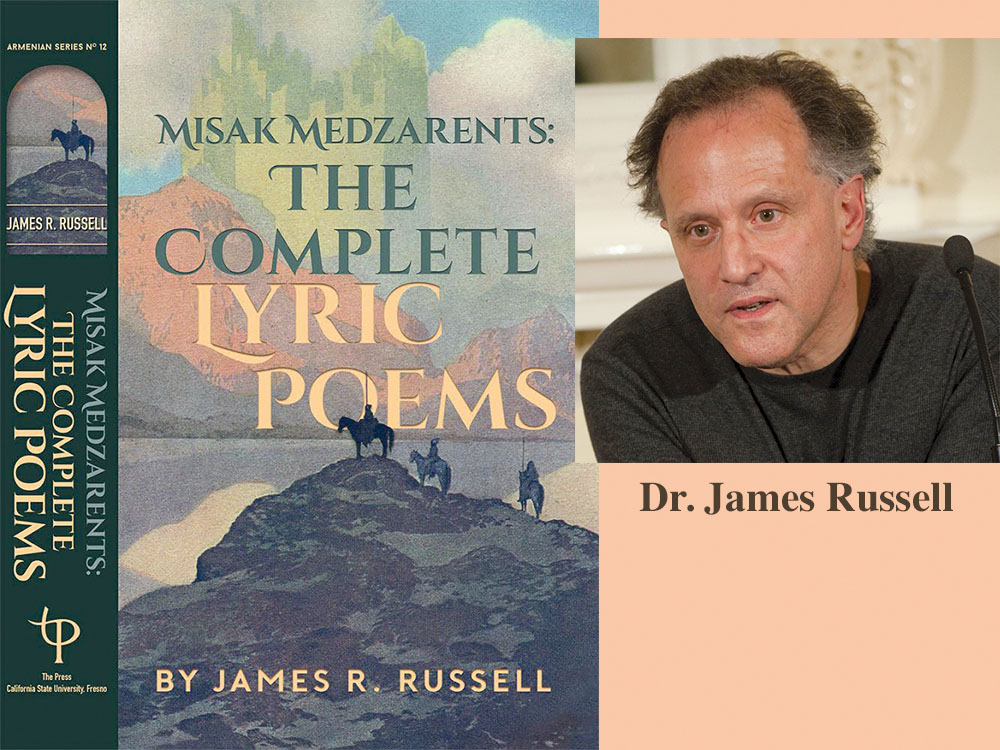

On Thursday, March 11, 2021, Dr. James Russell, Mashtots Professor of Armenian Studies, Emeritus, at Harvard University, discussed his newly published book, Misak Medzarents: The Complete Lyric Poems. Dr. Russell praised the significance of Misak Medzarents as a writer and poet.

“They [Misak Medzarents and Bedros Tourian] were alien to their own time. They were poets of the future trapped in a past to which their beauty was alien and unappreciated,” said Dr. Russell.

Misak Medzarents: The Complete Lyric Poems was published in 2020 as volume 12 in the Armenian Series of The Press at California State University, Fresno, under the general editorship of Prof. Barlow Der Mugrdechian.

Misak Medzarents, who Dr. Russell calls “dreamer, time-traveler, and magician,” was born on January 18, 1986, in the village of Pingian, in the Armenian Highlands, where he spent much of his early childhood. He and his family, aware of the rising chaos and massacres against Armenians in the mid-1890s, decided to move to Sepastia thinking that it would be much safer there for them. Safety was not guaranteed as they had hoped it would have been. Shortly after arriving there Medzarents was stabbed in the back by the son of a Turkish butcher. Dr. Russell stated that this “spurred his first very anguished poem, ‘Wound to the Body, Wound to the Heart,’ in which Medzarents is overcome by horror, not so much at the physical abuse but at the hatred that accompanied it.” Although most of his poetry is not political, Medzarents was very much affected in his life and in his work and by what was happening in the Ottoman Empire.

In the book, Dr. Russell presents nearly two hundred poems by Medzarents, translated into English, with the accompanying Armenian text in the appendix. The work includes extensive commentaries by Dr. Russell that investigate the complexities of Medzarents’ varied use of Armenian vocabulary.

“I think it has helped one to understand the poems better. Tracing Medzarents’ language allows us also to enter the laboratory of his mind, to explore the furnishings of his imagination, to browse in his secret inner library, that is to understand his creative process,” said Dr. Russell.

Most of Medzarents’ poems were of memories of his childhood in Pingian, of love, in which Dr. Russell explains that Medzarents was in “love with love itself,” although the traditional culture he experienced restrained him of his desires. According to Dr. Russell, Medzarents faced criticism for his poems about love. He added “the literary establishment, the cancel culture of the day, savagely attacked him as a decadent, a degenerate.” The restraint he faced created a sense of loneliness and anguish in which he “deploys against through a seductive vocabulary.”

In a specific example of the use of this type of vocabulary, Dr. Russell referred to the imprisoned King Arshak II’s final moments, prior to stabbing a fruit knife into his own heart. In those moments, Dr. Russell painted a picture of King Arshak II enjoying himself in the luxury of wine right before his fate. He says that Medzarents recreated a similar “Nocturnal Bacchanal” where the moment of dawn breaking on the Bosphorus drew a feeling for the moment to linger. Medzarents composed a word to describe the moment, “herahosan,” which he defines as “flowing with fire.” Dr. Russell explains that “water flows, fire does not flow, but it is the peculiar power of language that it can shape a word in which contraries exist in which fire does flow a word.”

Dr. Russell completed his book in the Judean Hills near Ein Karem in the summer, while he was teaching at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His motivation to initially start writing the book came when “it became clear towards the end of the 20th century that the Western Armenian language, that of everyday conversation in the diaspora communities here, had become [according to UNESCO] an endangered language. I felt it was a moral duty to devote serious attention to it accordingly.”

Misak Medzarents died of tuberculosis at the early age of 22. The same disease also claimed the life of Bedros Tourian fifteen years prior to Misak Medzarents’ birth. “Yeghishe Charents was in my humble estimation the greatest Armenian poet who ever lived, and he too also died early and tragically. He was only forty,” said Dr. Russell.

“Even if Medzarents had overcome his disease and lived on, it is very likely he would have been killed in the genocide of 1915 with the hundreds of other Armenian writers, artists, and thinkers of the capital whom he knew.”

Towards the end of the discussion, Dr. Russell read a few poems in both English and in Western Armenian, including that of “The Song of Life.” He concluded the presentation by reflecting on the Armenian Genocide and the atrocities Armenians faced in the early 20th century and connecting Medzarents to it.

“We tend to think of the past as having an inevitability, that whatever was happening in the Armenian community in Armenian life led up to 1915, but that’s not true,” stated Dr. Russell. “1915 was an interruption of life. There was nothing in Armenian life and culture that produced that destruction. On the contrary, it was perhaps because it was so thriving that those who were fearful or envious attacked it.”

“I think one should hold on to and recognize that this was a vibrant culture and that by studying it, by translating it, we are keeping it alive,” concluded Dr. Russell.

Misak Medzarents: The Complete Lyric Poetry is available through Abril Bookstore or the NAASR bookstore.

Hye Sharzhoom Armenian Action

Hye Sharzhoom Armenian Action