Carina Tokatian

Staff Writer

A nineteenth century Armenian migrant once wrote in a song, “I have left properties and orchards behind. Every time I say ahh, my heart breaks apart, oh crane wait for a second, let my soul hear your voice, oh crane, don’t you have any news from our country?” It was verses like these that characterized the experiences of an Armenian pandukht, a migrant from one of the eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire, who left their village to settle in cities such as Constantinople.

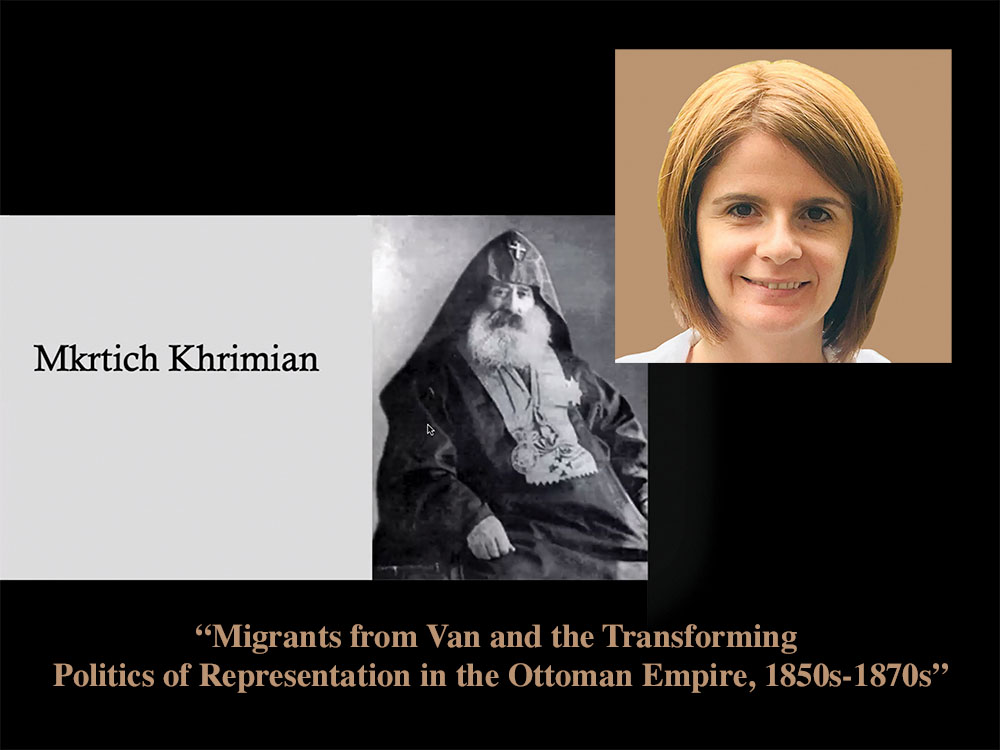

On Friday, March 19, the Armenian Studies Program and the Society for Armenian Studies (SAS) hosted a Zoom and YouTube lecture, “Migrants from Van and the Transforming Politics of Representation in the Ottoman Empire, 1850s-1870s” by Dr. Dzovinar Derderian.

Dr. Derderian is currently a professor at the American University of Armenia, a member of the editorial board of Études arméniennes contemporaines, and editor of the “Entries of the Society for Armenian Studies” website. She has previously written her Ph.D. dissertation on “Nation-making and the Language of Colonialism: Voices from Ottoman Van in Armenian Print Media and Handwritten Petitions, 1820s to 1870s” and has co-edited The Ottoman East in the Nineteenth Century: Societies, Identities, and Politics.

Dr. Derderian’s lecture centered around pandukhts, a multifaceted term that generally referred to Armenians who migrated from their homeland in the eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire and settled in urban areas such as Constantinople during the second half of the nineteenth century. She explained how this term was often associated with the vast number of labor migrants who settled in Constantinople. However, the term was also loosely applied to any Armenian who left their home. “Whether one was a merchant, a student, a clergyman, or a labor migrant, if the individual traveled away from Van and especially to Istanbul, they would often call themselves pandukhts” stated Dr. Derderian. Exploring archives from the AGBU Nubar Library in Paris and the Ottoman archives, Dr. Derderian’s research focused specifically on the prominence of pandukhts who migrated from Van to Constantinople.

Pandukhts typically resided in “hans” or large inns that remained a distance from the rest of the city. Typically, the residents’ dwellings were located on the second floor of these buildings while the first floor was dedicated to merchandise and newspaper publishing houses. As residents of hans, Dr. Derderian mentioned how pandukhts were exempt from taxes in Constantinople but still expected to pay taxes in their hometown. This further linked them to their home provinces. In addition, the emergence of steamships on the Black Sea abbreviated the journey between Van and Istanbul from seven or eight weeks to three, which strengthened the link between pandukhts and their villages.

Though perhaps seemingly depicted as uninvolved in the political sphere in articles, letters, songs, and poems, Dr. Derderian emphasized how “pandukhts were not just objects of paintings, photography, and literature, but they were also active subjects of history.” As the Ottoman Empire experienced the Tanzimat period, an era when governmental reform and the notion of voting circulated, the Armenian community begin to restructure and centralize itself under the millet system.

By 1863, the Armenian National Constitution was im-plemented, and the National Assembly was organized in Con-stantinople with the Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople at its head. Therefore, there existed many opportunities for pandukhts to become involved in the political sphere. As Dr. Derderian noted, men who paid at least 75 khurush could vote, and there was some representation of the eastern provinces in the assembly.

Hans also had a major influence on pandukhts’ political involvement. “Hans were a place where people could assemble to prepare a collective petition,” said Dr. Derderian.

Usually petitions sent from Van could take four to seven weeks before being read by the Patriarchate of Constantinople, whereas local petitions could be submitted in six days. This was due to the fact that scribes were easier to access in the capital, and petitions were much cheaper to submit locally.

In addition, Dr. Derderian highlighted how the pandukhts’ convenient proximity to publishing houses gave them immediate access to newspapers as well as opportunities to submit letters to the newspaper. Coffeehouses located at hans also welcomed political dialogues and petitions. Some of the concerns that pandukhts voiced through pe-titions pertained to ecclesiastical matters regarding the Catholicos, the Prelate of Van, and other church leaders.

Dr. Derderian underscored that clergymen did not simply have authority over spiritual matters but also collected taxes and unified families through marital alliances among their many responsibilities. For instance, the accusation that Catholicos Khachatur Shiroyan murdered his predecessor Bedros drew much attention in petitions and newspapers. “Petitioning was an important avenue to which the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire could make their voice heard to higher authorities,” Dr. Derderian stated. In contradiction to the notion that Armenians in the provinces were not in touch with Enlightenment ideals, she noted how the concept of popular representation or “the people’s voice” was evoked in petitions.

For instance, in a petition from 1871, she revealed how in contrast to previous petitions, the pandukhts did not “appeal to the mercy of the authority” such as the Patriarchate or members of the National Assembly. Instead, they appealed to “the law and their rights.” As she asserted, “it reveals the transformations in understanding of power, justice, and politics that were happening in this period.”

Ultimately as Dr. Derderian concluded, “the depiction of pandukhts’ lives in a vibrant setting of communication and sociability allows us to imagine them beyond their menial jobs, beyond the naiveté and poverty which literary works, newspapers, paintings, and books of the nineteenth century usually ascribed to pandukhts.” Instead, their presence in the Ottoman capital propelled political and social change.

Hye Sharzhoom Armenian Action

Hye Sharzhoom Armenian Action