Photo: ASP Archive

Christine Pambukyan

Staff Writer

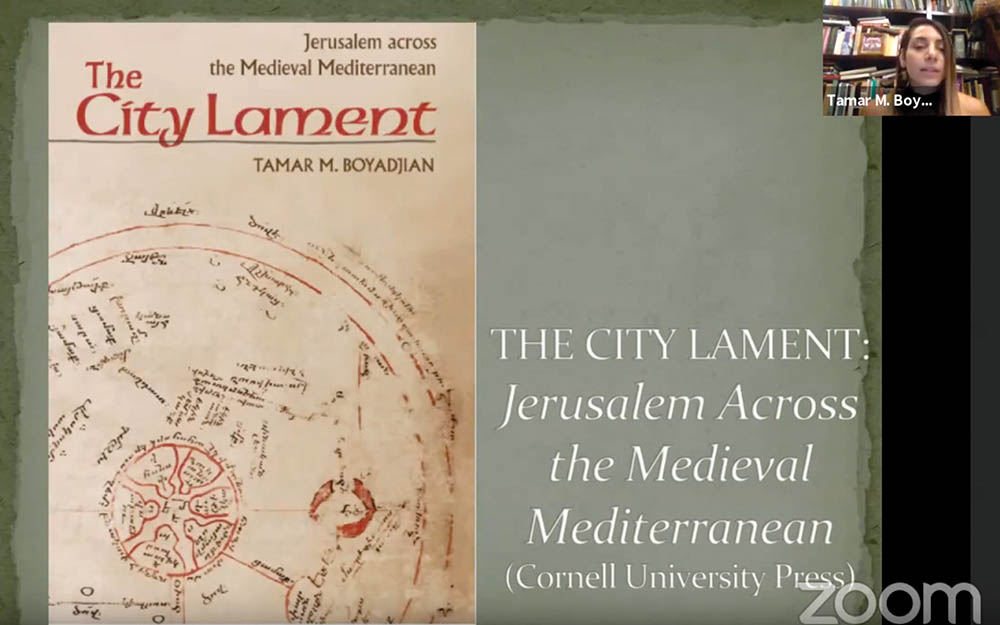

Dr. Tamar M. Boyadjian, Associate Professor of Medieval Literature at Michigan State University, teaches poetry and translation courses. Along with her teaching, Dr. Boyadjian is also an active scholar and wrote an award-winning book titled, The City of Lament: Jerusalem Across the Medieval Mediterranean in 2018.

On Thursday, September 24, 2020, Dr. Boyadjian evaluated how different cultures across the Medieval Mediterranean lamented the loss of Jerusalem through a virtual Zoom presentation of her book, The City Lament.

Photo: ASP Archive

Dr. Boyadjian began her presentation by reciting a creatively formatted poem she wrote in Modern Western Armenian titled, “Kentron.” She explained that during the time of the Crusades, Jerusalem was a city that fell under the control of many different cultures. As a result, members of various traditions, including Arabo-Islamic, Cilician-Armenian, and the Latin West, produced written lamentations to mourn the loss of Jerusalem.

“These lamentations modeled their compositions on ancient Mesopotamian city laments; specifically Akkadian, Sumero-Akkadian, and other Jewish concepts of mourning the loss of cities,” stated Dr. Boyadjian. Through their lamentations, each culture was able to further their reconquering of the Holy City by imagining how they desired Jerusalem to look geographically and feel spiritually.

Then, Dr. Boyadjian explained the origin and common attributes of city lamentation and why city lamentation rituals were conducted by female members of society. City laments originated in ancient Mesopotamia and within the Mediterranean world. An example of a city lament is the “Lament for Ur,” a Sumerian lament composed to mourn the loss of the city-state Ur to the Elamites in 2,000 BCE. Another example is the Akkadian epic poem, “Epic of Gilgamesh,” which includes references to the lamenting people of Uruk along with Gilgamesh. Also, in Europides’ tragedy, “Troidus,” which was produced in 415 BCE, during the Peloponnesian War. The play tells the story of the capture of Melos, an Aegean island, as four Trojan women lament the loss of Troy. Furthermore, Homer’s Odyssey also acts as a lamentation for the city of Troy.

“Lamentation was an unquestionable part of the ancient ritual culture, particularly in the sharing of community grief,” stated Dr. Boyadjian. Females who conducted the rituals acted as intercessors between the material and spiritual worlds. Their loud cries and self-lacerations were often performed at funerals and imbued emotions to those around them. These rituals were conducted by many cultures, including the Hittites and the Romans. Also, men of Sumeria and Athens would dress as females to perform lamentations as an outlet for expressing their emotions.

Dr. Boyadjian then explained how the view and treatment of city lamentation evolved in the Monotheistic world. Over time, lamentation began to be viewed as a threat to the patriarchal roles in society and began to be prohibited by ancient societies. The Latin Church and the Arabo-Islamic Tradition condemned lamentation. This is reflected by the lack of lamentations translated from the new and old testaments of the Bible. Lastly, the role of city lamentation for the Eastern Christian Church, specifically for the Armenians, evolved into a form of hymns and psalms sung by the church. The priests took on the role of mediums between the material and spiritual world and songs were sung to mourn the loss of cities, kingdoms, and people throughout Armenia’s long and tragic history.

Dr. Boyadjian concluded her lecture by reciting an English translation of her poem, “And if you reap it, you will create; you birth it, it guides you. Isn’t that the center? And if it moves or changes a ray of light, is it possible to know where the center is? And if you go, you will return. It’s lasting. Would you have wanted to know, is this the center? And if you forget, you’ll remember; it’s eternal. Would you have asked, ‘Are you the center?’”

A recording of this lecture, along with other lectures of this semester, can be found on the Armenian Studies YouTube channel: bit.ly/armenianstudiesyoutube.

Hye Sharzhoom Armenian Action

Hye Sharzhoom Armenian Action