Carina Tokatian

Staff Writer

The French philosopher Roland Barthes once wrote, “When we define the photograph as motionless images, this does not mean only that the figures it represents do not move; it means that they do not emerge, do not leave: they are anesthetized and fastened down, like butterflies.” Ironically, as Dr. Zeynep Devrim Gürsel highlights, the Ottoman Empire’s use of photographs as an instrument of enforcing the permanent emigration of many Armenians presents a paradox to Barthes’ statement; migration is rendered in the stills.

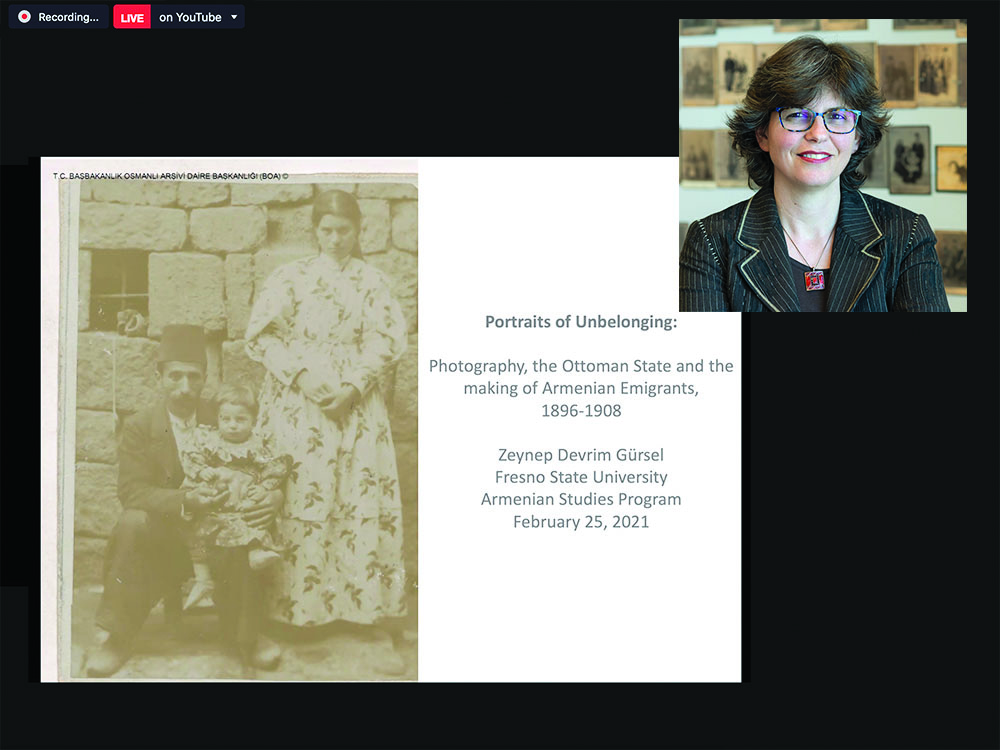

On the evening of Thursday, February 25, the Armenian Studies Program sponsored a virtual lecture presented on Zoom and YouTube by media anthropologist Dr. Zeynep Devrim Gürsel. The topic of her lecture was “Portraits of Unbelonging: Photography, the Ottoman State and Armenians Leaving for America 1896-1908.” Dr. Gürsel is currently Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology at Rutgers University. She has previously authored Image Brokers: Visualizing World News in the Age of Digital Circulation and directed the 2009 documentary Coffee Futures.

It was after a frustrating research day that Dr. Gürsel initially took interest in photographs of Armenian families who emigrated from the Ottoman Empire during the reign of Sultan Abdülhamid II. After seeing a couple of these portraits, she recalled, “I just was mesmerized by the photographs, and I couldn’t stop thinking about them.” She wondered who the photos belonged to or who might appreciate them. “I felt compelled to bring them into the present day and take them out of the state archives in Istanbul and into Armenian communities” she stated. Knowing little about Armenian history at the time, she credited Alice Kaloustian, the mother of a dear friend, for helping her initiate the project. “Alice was extremely supportive and within hours she had made key introductions to several people,” she recalled. She added that “her living room has become my home base in California, and she remains a very important touchstone every step of the way in this project.”

At the time when the photographs were taken under the Sultan’s leadership, there was much political turmoil in the Ottoman Empire. Greece and Bulgaria had become independent nations and the influx of Muslim refugees from the Caucasus and the Balkans affected the political landscape of the region. “It was a time when individuals were shifting from being considered and considering themselves as subjects to becoming citizens,” Dr. Gürsel noted. She added that this especially served as an intriguing moment to examine photography “since even when they depict types or groups, photographs always index individuals.”

Overall, Dr. Gürsel managed to collect 109 photos from Ottoman State archives in Istanbul. These came from various files such as the Ministry of Interior or Foreign Affairs folders. Other photos were stand-alone archives. Each one depicts a variety of individuals – men, women, family elders, children, infants, urban elites, peasants, and the like. The flip side of each photograph contains individual’s names, ages, always the fathers’ names, and the home villages of the pictured. Some even noted ties the photographed individuals had to those who had migrated before them.

Dr. Gürsel emphasized the fact that these are “certainly not family portraits taken to commemorate a moment of togetherness.” Rather they served as “a form of exclusion.” The Armenians who posed for these pictures had renounced their Ottoman nationality and promised to never return to the Ottoman Empire. As she noted, “the operative temporality in these photographs is not so much what has been but what must never be again.” Displaying a photograph taken in Bitlis, Dr. Gürsel explained how her use of the phrase, “portrait of unbelonging” is meant to convey that the photo “captures the process of making this family into emigrants and unmaking them as Ottoman nationals.”

From 1896 to 1908, these photos were required of Armenians wishing to leave the Ottoman Empire, usually through one of four main ports: Samsun, Trabizon, Mersin, and Iskenderun. Prior to this period, Armenians needed to obtain permission individually from the Sultan in order to emigrate. However, his 1896 decree permitted Armenians to leave as long as they obtained a document from the Patriarch and two copies of a photo to be sent to Constantinople. In total, about 5,000 individuals emigrated to America under this process, submitting more than 1,500 portraits to Constantinople.

The regulations made no distinction between the various Armenians who were to go through this process whether they were Apostolic, Catholic, or Protestant. Even Assyrians who were leaving in order to marry Armenians already in America had to undergo this process of renouncing their nationality if they desired to leave. However, the regulations applied only to Armenians as Dr. Gürsel stated that Lebanese Christians were required to do the exact opposite. They were to pledge to keep their Ottoman nationality in order to travel.

Equating the photographs to “mug shots,” Dr. Gürsel asserted how the portraits were “motivated by suspicion” and served as “anticipatory arrest warrants.” After the growth of political organizations such as the Hnchak Party and the Dashnak Party, Ottoman leaders feared that Armenians would revolt. After all, as an “American fever” surged in the 1880s and 90s, many Armenian emigrants settled in American cities such as Fresno, Boston, Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles. So, there was a fear among the Ottoman Empire that Armenians would return to their homeland as revolutionaries. As Dr. Gürsel explained, “it was not that they wanted them to leave; it was that they did not want them to return politicized.” Therefore, the police and even many successful Armenian photographers captured these photos and required them at ports if Armenians were to board any ships. “The passports issued to these Ottoman Armenians are unique in that they permit travel but prohibit return,” she mentioned.

In the second half of her lecture, Dr. Gürsel stated how she sought to capture the “double-sided history of migration.” Comparing her project to the photographs, she explained how the project faces “two directions: the Ottoman past in which the photograph was produced and circulated and an American future in which the lives of the subjects in the photographs unfolded.” With this in mind, she shared how the project “meant taking copies of the photographs out of the archive and into the world, out of Ottoman bureaucracy and into the life experiences of migrants and their families.”

In total, Dr. Gürsel managed to collect migration information for 62 families by searching through ship manifests, tickets, arrivals on Ellis Island, etc. Thanks to the tedious Ottoman interception of documents, she was also able trace letters of Armenian-American immigrants corresponding with other Armenians in the Ottoman Empire such as Cercis Gürjian who humorously describes Fresno in a letter: “this place has become Turkey.” In addition to her collection of documents, Dr. Gürsel has been afforded the opportunity to meet with living descendants of fourteen families whom she has traced. One such family is Hosrof Kevorkian’s, who moved to Fresno and established the Valley Fruit Co.

As Dr. Gürsel stated in her conclusion, “while the Ottoman State’s instrumental view of these photographs anticipated a very particular future intended to be prevented by these very portraits, I believe the trajectory of these photographs and that of the subjects within them is more radically open.”

Hye Sharzhoom Armenian Action

Hye Sharzhoom Armenian Action